Bringing hope and boxing to young people in Phoenix

by Gus ContrerasPeter “The Punisher” Chavez didn’t have it easy growing up as a kid in Phoenix’s largely Latino Westside neighborhood. He and his five siblings were raised by their single mother, who had to hold down more than one job to support them. In many ways, the obstacles he faced as a kid paved his path to the boxing ring.

Listen to this story

During a neighborhood football game, Chavez fought off one of his bullies. One of the men who pulled them apart gave Chavez his business card and told him he should consider boxing because he had the heavy hands for the sport. So he tried it.

“It was a rude awakening because I was a street fighter,” said Chavez. “I thought I was a tough guy and all that.”

The sport’s strict discipline kept him engaged. He said boxing challenged and motivated him in ways he never experienced.

Chavez went on to lead a successfiul amatuer career that included winning a Golden Gloves title and state championships. He earned the nickname “The Punisher” because he “punished” bodies during his fights. Chavez aspired to become a professional fighter, but his plans changed when his family life took a turn.

“My ex was actually raped,” said Chavez. “And that’s later on when she left, because she turned to drugs. So it was just me raising my babies and then working nights, six days.”

Chavez worked overnight shifts to support his two kids and kept training in boxing.

“I would make myself sick because [of] very little sleep,” he recalled. “And [then] I’m like, I can’t do this. I’m putting myself at risk, my kids. So I gave it [boxing] up so I could concentrate on my kids and focus on being a dad.”

One day his son Conrad Chavez picked up a local newspaper that was sitting around in their house. The paper had an ad for a Toughman Competition. His son insisted he enter the contest with a $2,000 winning prize. So Chavez thought about it.

“I’m like, Shoot, why not? I’m in great shape. I’m 39, but I feel like 29,” Chavez remembered thinking to himself. “So I did it and won. I had to fight three times in one night and I won that championship.”

That was enough to make him fall in love with boxing all over again.

“It’s in your blood,” said Chavez. “Once a fighter, always a fighter. Once a warrior, always a warrior.”

“It’s in your blood,” said Chavez. “Once a fighter, always a fighter. Once a warrior, always a warrior.”

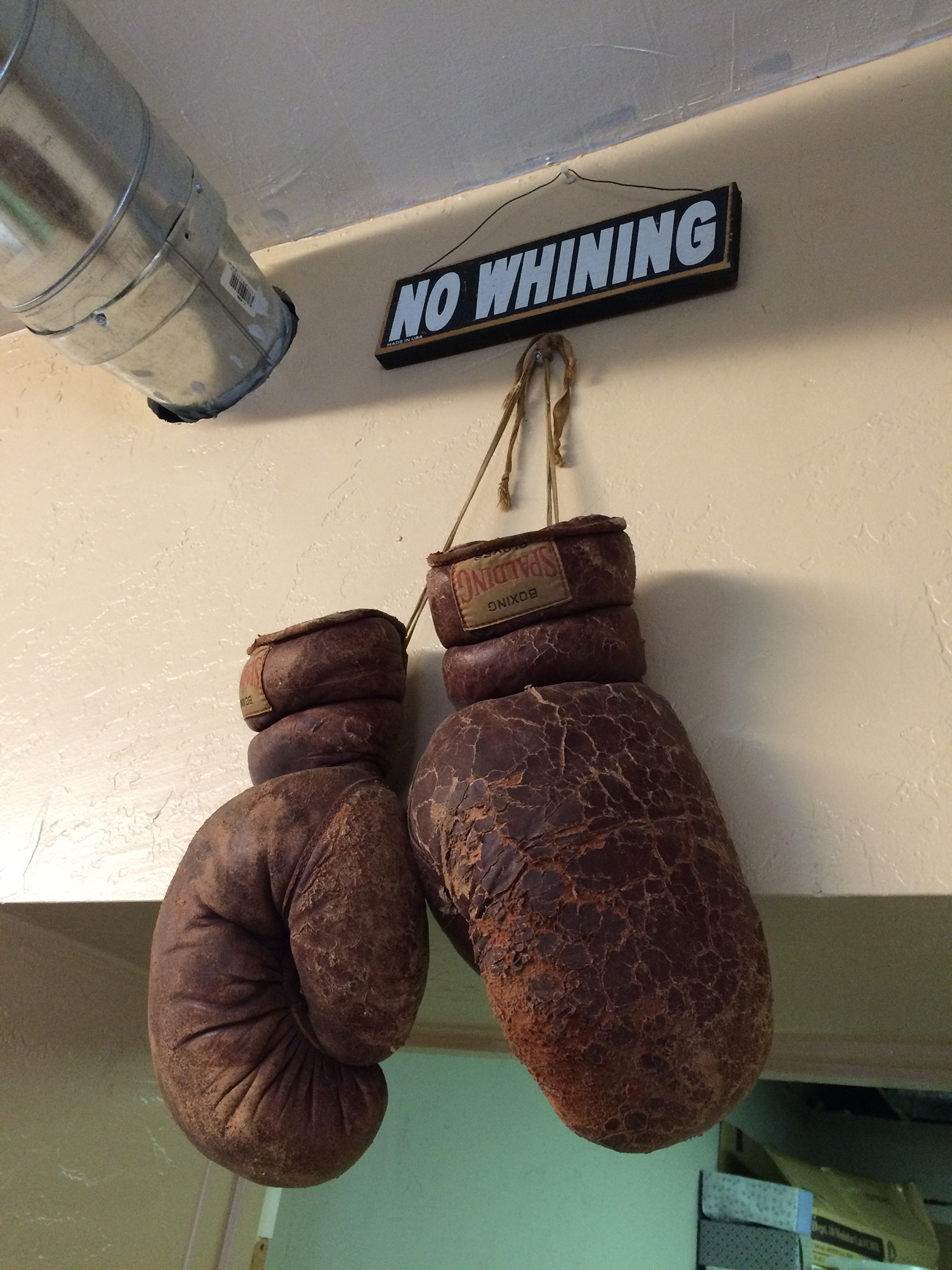

Chavez said he was tired of his job stocking inventory at an electronics store, which he described as “back-breaking.” He craved a career change, so he leased a small room at his local church to become a personal trainer, which allowed him to stay in boxing. His son started to bring friends to the gym to learn how to box. Chavez said he felt like he couldn’t turn them away and didn’t charge them any money.

“I knew there was more [to it], not just the boxing,” said Chavez. “I wanted to help them, talk to them. And that’s what I would do with a lot of kids.”

A stranger took notice and offered to help him start a nonprofit foundation that would allow Chavez to keep training kids to box.

Gang members retaliated and vandalized the church when they found out Chavez was encouraging kids to stay away from the dangers of gangs and drugs. For a few years, the gangs followed Chavez. The Arizona Criminal Justice Commission reports the state has more than 32,000 gang members.

“I would just tell them, I’m not going anywhere, I’m not scared. You can do whatever but I’m not leaving. This is what I’m supposed to be doing, you’re not going to stop me,” he remembered telling them.

These days the gangs have left Chavez alone and he continues to train young boys and girls through the Chavez Boxing Foundation. He currently has 20 students.

A stranger took notice and offered to help him start a nonprofit foundation that would allow Chavez to keep training kids to box.

Gang members retaliated and vandalized the church when they found out Chavez was encouraging kids to stay away from the dangers of gangs and drugs. For a few years, the gangs followed Chavez. The Arizona Criminal Justice Commission reports the state has more than 32,000 gang members.

“I would just tell them, I’m not going anywhere, I’m not scared. You can do whatever but I’m not leaving. This is what I’m supposed to be doing, you’re not going to stop me,” he remembered telling them.

These days the gangs have left Chavez alone and he continues to train young boys and girls through the Chavez Boxing Foundation. He currently has 20 students.

Gus Contreras

Gus Contreras was born and raised in El Paso, Texas, and is a first-generation American with parents from Mexico. He’s a producer for All Things Considered at KERA in Dallas, TX.

A sports nut, he enjoys traveling and spending time with friends and family. When he’s not trying to cook Mexican food at home, Gus enjoys finding new taco places in North Texas. If the Dallas Cowboys or Arsenal FC are playing, you can usually find him glued to his tablet watching — that is, unless he’s working on a story.